I’ve been reading a lot about boundary objects lately. Boundary objects are loosely-defined artifacts, categories, or documents that facilitate partial cooperation across communities of practice (Star and Griesemer 1989). The basic concept is that you can have ‘collaboration without consensus’. It’s not necessary to fully agree on the meaning of a boundary object for it to be a useful tool for cross-disciplinary collaboration. So, for example, prototypes in software development can serve as boundary objects to bridge knowledge boundaries between software developers and UI designers (Huber et al 2019).

Reading about boundary objects got me thinking about when I used to play jazz music, and how collaboration works in music improvisation. Jazz is inherently fluid and dynamic. This is exactly what makes it such an exciting artform. In many ways, jazz is the process of creation rather than the music itself. Louis Armstrong said ‘Jazz is what you do with music’. It’s a real-time collaborative project where multiple people engage in the process as a team to create something new and exciting. The excitement of making the music, and of listening to it, comes in part from this meeting of different people who have a shared reference point which is used by all participants during collaboration. This shared reference point is known as the lead-sheet.

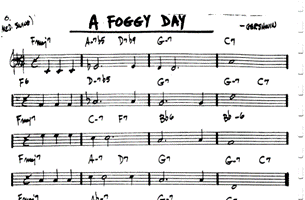

A lead-sheet is piece of paper that the musicians each share when working together. Lead-sheets can range from a barebones chord structure like the often-used lead-sheets from The Great American Songbook, like George Gershwin’s Broadway show tune A Foggy Day (Fig 1), to a detailed, intricate description of all the notes and articulation. It can even just be a symbol or shape, like Anthony Braxton’s Kandinskyesque lead-sheet for Composition #10 (Fig 2). The skill of the jazz composer is to understand how much shared meaning needs to be inscribed in the lead-sheet for the process of collaboration to be effective. To do this, the composer needs to understand the shared meaning that overlaps between each band member, which gives the composer a sense of how much, or how little, to write into the lead-sheet to stimulate an engaging experience for the performer and the audience. The usefulness of this loosely-defined document comes from its ability to facilitate collaboration across the sometimes contradictory influences of the band members.

Fig 1: Gershwin’s A Foggy Day lead-sheet

Fig 2: Anthony Braxton’s graphic lead-sheet for Composition #10

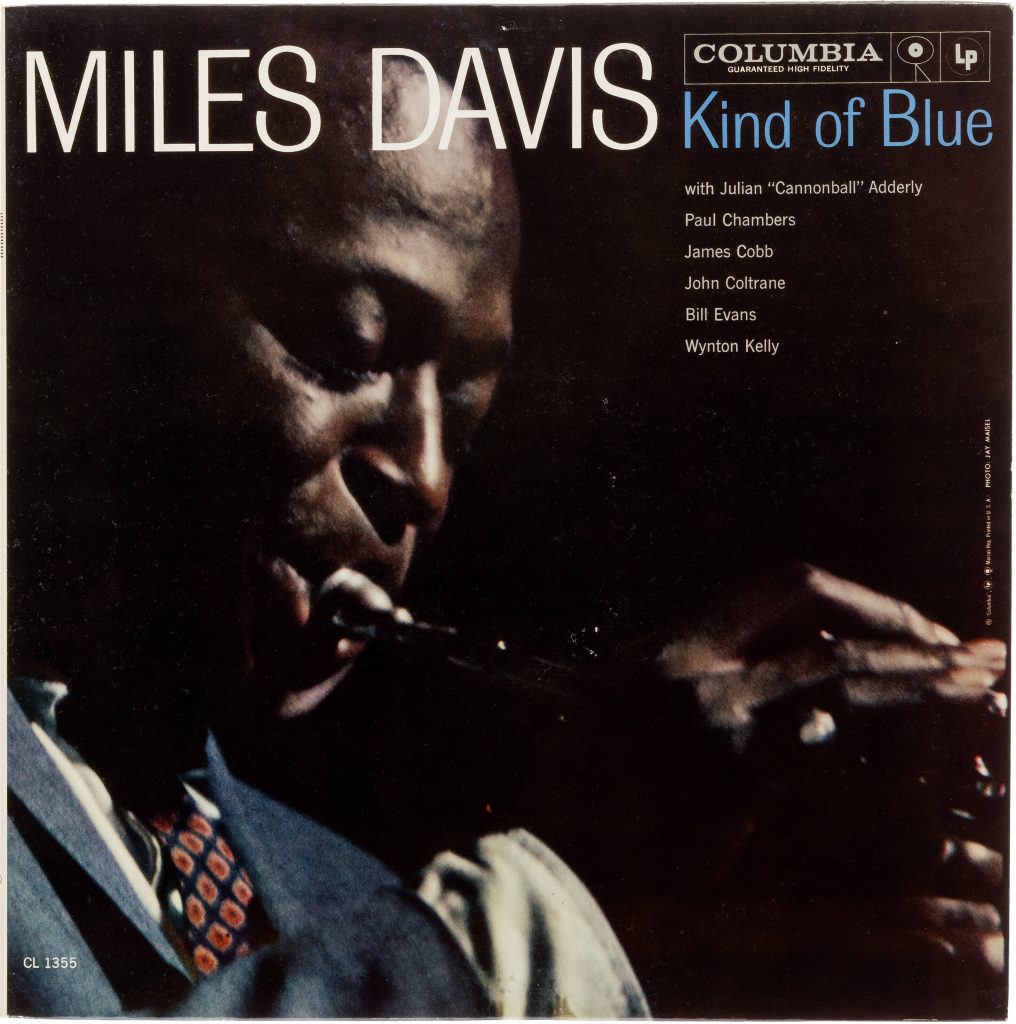

Fig 3: Miles Davis: Kind of Blue

In 1959, Miles Davis recorded his iconic jazz album Kind of Blue. The album opens with a piece titled So What. If you listen to the recording, and then look at the lead-sheet (Fig 4), you’d almost be disappointed to see how little is actually written on the lead-sheet; Just a simple melody and some chords every few bars. There’s almost nothing there!

Fig 4: So What lead-sheet with Bass melody and Horn chords

But that, of course, isn’t the full story. Miles knew exactly what he was doing when he wrote that lead-sheet, and when he hired the musicians for that recording session. He picked musicians who were similarly interested in the process of exploratory music-making. Davis knew exactly how much or how little needed to be on that lead-sheet for this process of jazz creation to unfold between the band members. While each of the players have very different backgrounds and influences, there was an overlap that the lead-sheet taps into. Pianist Bill Evans, who lays the sublime piano introduction to So What, once said that ‘jazz is not a what, it is a how’. Part of the genius of Miles Davis is that he constructed the loosely-defined lead-sheet with as little detail as was needed to stimulate the collaboration. John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley both play saxophones on the recording, but their playing style are so very different. This lead-sheet functioned as a boundary object shared by these musicians, allowing for enough overlap between them while still giving enough scope for interpretive flexibility to make the collaboration fruitful for everyone involved.

Nicolini et al (2012) write about how boundary objects function in cross-disciplinary collaboration. They have the capacity to serve as bridges between social and cultural worlds. Their fluidity of meaning can be an advantage for creating this cross-disciplinary work, which is certainly the case with So What. It’s also interesting to think of how the meaning of a boundary object is co-constructed through iterative cycles. So, rather than saying that So What was composed by Miles Davis, it’s probably more accurate to say that the So What lead-sheet was a boundary object that enabled the quintet to coordinate and compose collectively, co-constructing the meaning and capturing this in a studio recording. (Although, for the purposes of copyright, I’m sure that Miles would have disagreed with that!).

There’s a lot more to unpack here about how a lead-sheet functions as a boundary object in interdisciplinary teams, including the question of how much the meaning of the boundary object should be fixed to begin with.

When introducing a boundary object, it’s important to understand the overlaps across communities of practice. There doesn’t need to be complete consensus about the meaning of the boundary object, but there needs to be some overlap for fruitful collaboration. The purpose of a boundary object is to facilitate collaboration. These objects can have different meanings across the various communities, but their structure is common to all groups so they are recognizable and useful. In this case, Miles Davis intentionally created the So What lead-sheet as a boundary object for collaboration, and it was incredibly effective because of his understanding of the overlaps between the communities of practice. Since he wrote the lead-sheet, So What has been played thousands of times by different groups, each time producing a different process, a different collaborative outcome, but always tapping into both the shared and differing meaning that musicians give to the lead-sheet. As with interdisciplinary collaboration, while the end result of the process might not always be clear from the outset, a useful boundary object lets the participants work together to ‘collaborate without consensus’, and to produce novel, interesting outcomes.

References

Huber T, Winkler M, Dibbern J, Brown C (2019) The use of prototypes to bridge knowledge boundaries in agile software development, Information Systems Journal, Wiley Publishing.

Nicolini D, Mengis J, Swan J (2012) Understanding the Role of Objects in Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration, Organization Science, Informs Publishing

Star and Griesemer (1989) Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39, Social Studies of Science, Sage Publishing.

Images

Braxton A (1982) Composition #10 graphical score, https://www.criticalimprov.com/index.php/csieci/article/view/462/6400

Davis M (1959) Kind of Blue, Album cover, Columbia Records

Davis M (1959) So What lead-sheet, in Real Book, Sher music publishers

Gershwin G (1937) A Foggy Day lead-sheet, in Real Book, Sher music publishers

Recordings

You can listen to So What here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ylXk1LBvIqU